Pass the bonus please: energy bosses’ pay is unmoored from earnings

By Rachel Williamson

Two of Australia’s largest listed energy companies have been delivering record earnings to shareholders in recent years, but CEO pay overall is unmoored from the returns they are presiding over. And it’s not because shareholders are worried about regulatory fallout from the federal government’s ongoing war with the energy companies.

Those pay packets are linked to the climb up the greasy corporate pole and investor-related benchmarks, not what happened in the last 12 months, says veteran energy expert David Leitch.

“Management remuneration is carefully considered by corporate investors,” he said.

“Some of them spend a lot of time making sure that incentives are related to the goals that fund managers look for, such as sustained performance over time.”

But energy CEO remuneration is on par with their peers on the ASX200: big bonuses and stagnant salaries are the norm.

What political pressure?

Super profits by the major gentailers, combined with high retail power bills, have drawn the gimlet eye of the government.

But that pressure is unlikely to have much of an impact on their bottom lines — or executive pay.

Profits began to surge at the big gentailers AGL, former state-owned enterprise EnergyAustralia, and latterly the Snowy Hydro-Red-Lumo combination, after 2016 when power prices began to spike.

Origin has caught up with that trend after dealing with the fall-out from the Australia Pacific LNG investment.

Even though an ACCC report this year found that 43% of a retail power bill was due to network costs, the government is aiming to reduce costs solely at the household level.

Energy Minister Angus Taylor’s plan for a default energy price offer is raising strong concerns that it could force smaller players out of the retail market, leaving the space open for the market behemoths.

One theory is that a very low default offer would benefit the biggest players with economies of scale, and the retail energy market will return to being dominated by the big four players, says Grattan Institute energy fellow Guy Dundas.

A return to a market oligopoly is likely to diminish government, and potentially investor, demands for moderation at the top.

Enjoying Australian Energy Daily’s introductory newsletter? Please help us spread the word by forwarding this email to your colleagues.

Who got what in 2018

Of the ASX’s six billion-dollar energy businesses, AGL boss Andy Vesey and Mercury NZ chief Fraser Whineray both watched their pay packets slide.

For Mr Vesey, it was a result of a shareholder vote against executive remuneration in 2016. The board, on notice the following year, reduced his incentives by $460,000 to lower the risk of losing their owns jobs in the event of a second strike.

Mr Whineray had to cope with a 4% pay cut to $1.8 million because his long term stock incentives didn’t vest.

Genesis Energy’s profits plunged 86%, yet chief Marc England got a nice 48% bump in his total pay for the year. The company said it was the underlying earnings, which beat expectations, that mattered.

Origin Energy’s Frank Calabria presided over a return to black, a colour the books hadn’t seen since 2014, following the expensive investment in the Queensland APLNG plant just before oil prices dived.

They moved from a $2.2 billion loss in fiscal 2017 to a $218 million profit.

Yet his pay, of which over two thirds was bonus, only rose 11% from the year before.

Keeping up with the Joneses

Energy boss earnings are on par with their ASX peers — in terms of bonuses at least.

The vast majority of energy CEO pay came in the form of bonuses: 30-70% of remuneration for the top dogs came in the form of long and short term stock incentives.

In the ASX100 more generally, about one in three CEOs receive 80% of their salary from incentives.

“Bonuses paid continue to be near the top end of their maximum potential. ASX100 CEOs are more likely to lose their job than their bonus,” said a report into CEO pay in 2017 by the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors (ACSI), released this year.

In fiscal 2017, average take home pay for ASX100 executives was $6.2m. Only Mr Vesey achieved the average that year.

Base pay between 2017 and 2018 for chiefs at all six listed energy majors was flat or slightly higher the following year.

ACSI says average fixed pay in 2017 rose just under 1 per cent to $1.9m and reflects the fact that new CEOs are coming in on lower fixed pay than their predecessors.

Meridian’s new CEO Neal Barclay was appointed on almost $200,000 less for the six months he worked than his predecessor Mark Binns, who walked away with $1.2m for his six months of labour.

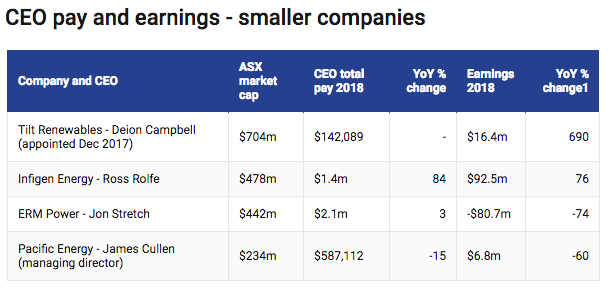

At the smaller end of the market are generators like Tilt Renewables, Infigen Energy, ERM Power and Pacific Energy.

ACSI says it’s harder for executives at smaller companies to achieve their bonuses in the face of bad financial, and that appears to be born out in these companies — to a certain extent.

James Cullen at Pacific Energy took a 15% pay cut, coinciding with a 60% fall in earnings and earnings per share for his stakeholders. But he still received his entire bonus: the cut was due to a slight base salary decrease and a reduction in the number of options he was given.

Jon Stretch at ERM managed to scrape in a slight pay rise — 3% — by earning all of his bonuses, even though the books showed a massive loss for the year.

Let the good times roll?

On the horizon is a range of emerging risks for energy companies, which are likely to start to put pressure on corporate, and CEO, earnings.

Leitch says the generation market is becoming more competitive as a rush of new, sophisticated investors and small companies move into wind and solar generation, and rooftop solar installations continue apace.

The energy market operator AEMO is forecasting demand to remain flat until the mid 2020s, yet the country has a surfeit of proposed new generation.

The country had 50.5GW of installed power capacity at the end of October, 6.1GW of committed projects and a whopping 48.9GW of proposed projects, according to energy market operator AEMO.

“It won’t be a disaster for any of them, but I doubt it’ll be as good as the last few years,” Leitch said.

Rachel Williamson is a journalist for Stockhead, where she covers capital markets and energy. Her work on energy and economics in the Middle East and Africa has appeared in Foreign Policy, Bloomberg Businessweek, the Financial Times’ This is Africa, Forbes and others.